|

| Betty McNeal Wheeler • 1972 |

Betty McNeal Wheeler was born into an important St. Louis family, one that

encouraged and supported education and community service as essential to a

distinguished life -- what you have, you share; what you get from others, you

pay back through appreciation and service; and what you see as unjust, you

work to change. Betty grew up with this as a deeply ingrained part of her life

concept, and she brought these concepts to the table, when she developed the

concept for one of Missouri's most successful high schools: Metro Academic and

Classical Academy.

|

| T.D. McNeal (source) |

Founding Metro High School

Betty, a graduate of Sumner High School in the city of St. Louis, and then of St. Louis University, began her career as a teacher at Gundlach Elementary, in the St. Louis Public School district. She later worked at the Northside Reading Clinic, and at Yeatman Elementary, and was the Coordinator of the SLPS work-study program at Ralston-Purina Company, when she began work on laying the foundation for Metro High School, in 1971. The school began as one of several innovative new programs being tried out in the St. Louis Public School district, which were initially described in a 1971 newspaper article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

This is how Metro began, but it evolved over the years, always under the careful guidance of Betty's ideas of how it could best serve the students and their community.

The 1970s (The Chouteau Avenue years)

1971 was the planning year. The St. Louis Public Schools were looking for ideas for innovative new school concepts, and Betty had been intrigued by readings and workshops about a few other schools around the country, that were experimenting with the school-without-walls concept.

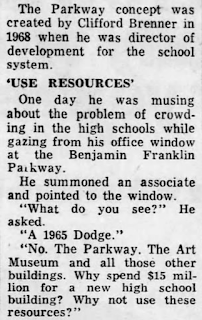

Philadelphia had its Parkway High School Without Walls, whose name was inspired by the view of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway...and the Art Museum...and all of the buildings around the city of Philadelphia... that Clifford Brenner, director of development, could see from his office window, and that he suggested should be, could be, used as the "classroom" for motivated students.

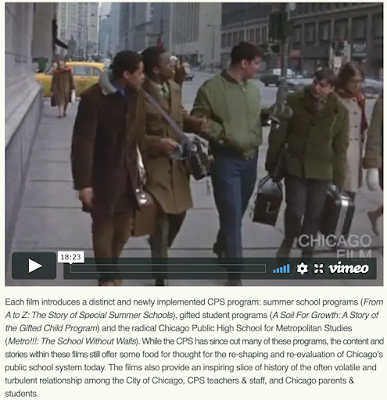

Chicago had its own Metro High: Chicago Public High for Metropolitan Studies (though it appears that everyone called it, lovingly, Metro!! The School Without Walls!). The 1970 video, here, on the Chicago Film Archives web page, describes the early structure for Chicago's Metro High. One of the adults interviewed, mentions that its philosophy is to combine the interests and ideas of students, with the experience and judgement of what works, of the educators, emphasizing that students have great input, but do not "run the show", as some community members were fearful would be the case. The commentary in the video takes great pains to emphasize the community nature of Chicago's Metro High, that exploring and learning from what is available in the community, and learning to appreciate the community, were at the heart of the tenets of the school.

Unfortunately, though, these schools had begun to have problems in their early years, and experienced difficulties throughout the years that they were open, trying to tweak and re-structure, to keep students, parents, and the district, interested, and to prove that these were viable, laudable educational experiences. They appear to have been that for some students, but not for others. Both schools eventually were closed.

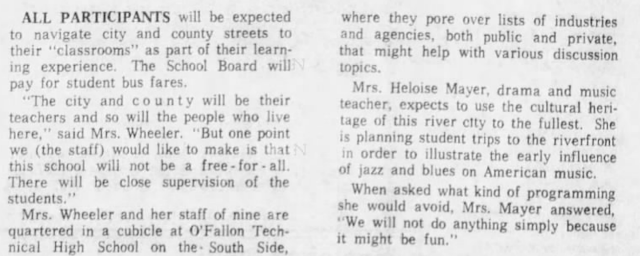

Betty Wheeler's strength, in designing St. Louis's Metro High, was in her innate understanding that this concept could work, but only with more careful planning, and with a constant eye on what was working, and what might not. She said, in an interview in April of 1972, about the upcoming opening of the school, in fall of 1972, that she felt that the key to putting together a really viable version of a community-based school without walls, was in the planning, and that she felt that the reason that other schools that had tried this idea, had not worked out in the long run, was because the staff was not given enough time to fully flesh out the plans, carefully. Here are a few snippets from the newspaper article, St. Louis To Try Out A Classroom As Big As The City, published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 11, 1972:

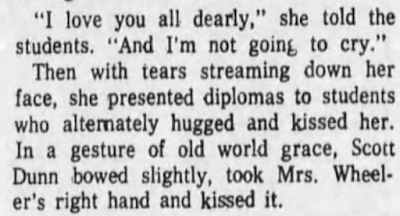

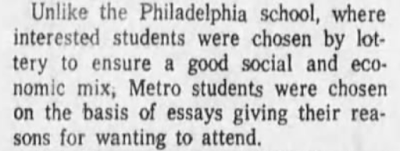

One of the key areas to which Betty gave a good bit of thought, was the idea of who would be accepted as students in St. Louis's Metro High. She understood that one of the weaknesses of the Philadelphia program, for example, was how it got its students. That school used a simple lottery system, and students were referred if they seemed to have a difficulty accepting the norms of a traditional school. Not as much thought seemed to be given, in Philadelphia, to the motivation and abilities of the students. Betty's Metro High would more carefully organize their selection process: the school would focus on students who were deemed most capable of taking advantage of the freedoms and unconventional structure that the school without walls would provide. They needed to show a strong academic ability, along with a heart that yearned for exploration and a soul that would soar when given the opportunity to grow through a non-traditional structure. Students were asked to write essays about why they felt that Metro would be a great fit for them, and test scores and personal references from their current schools, were evaluated. Additionally, Metro was meant to be a place to bring together and celebrate students from the black community, and from the white community, from all over the city, at a time when racial integration in the schools was a new concept, striving for success, and desperately needed in the St. Louis community. This was also a time when the voices of women in the United States were beginning to be heard, and this, too was to be part of Metro High's mission: to celebrate all segments of our society, by living and working together, thereby providing a natural growth of appreciation and respect for each other.

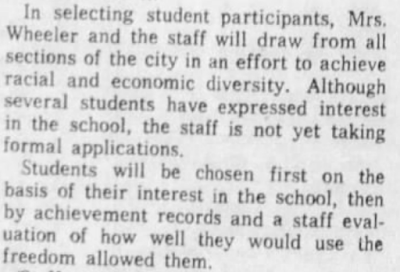

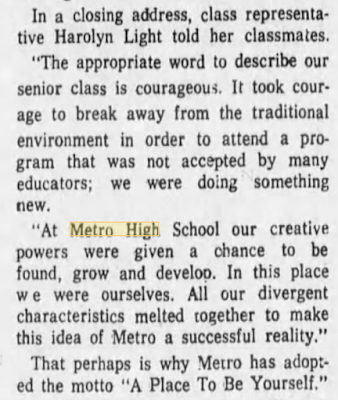

And, from a 1974 article about Metro's first graduation:

This was another uncanny part of Betty Wheeler's character, and a big part of what she, personally, brought to the heart of her Metro High: Betty had a way of knowing how to inspire excellence while also requiring excellence... students (and staff) were not brow beaten, but they were so lovingly appreciated and praised when they put forth every effort possible, that they wouldn't think to give less than their all. All of this was beautifully portrayed in an article in 1974, about Metro's first graduation. The whole article is available here, but some of its key points are shown in these snippets:

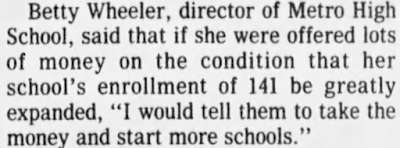

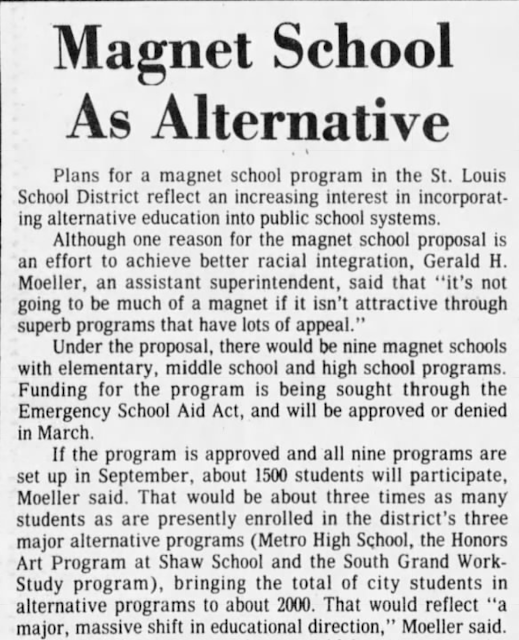

As Metro continued its School Without Walls concept throughout the 1970s, it grew to accept all four grades (its first years saw the inclusion of students only in the 11th and 12th grades), but it was billed as an Alternative School, not a Magnet school, as the Magnet School program did not begin in St. Louis until late 1976. Two articles in the February 1, 1976 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, both on page 3G, discuss Alternative Schools, and mention Metro. Betty is quoted in this extensive article about Alternative Schools, about the concept of keeping the schools small -- this was always a key issue for Betty, as she understood, from research as well as practice, that students were best served in small schools, rather than in large ones.

The second article on that page (Magnet School As Alternative) describes the plans for the upcoming Magnet Schools program, and the value of incorporating the existing alternative programs, into the Magnet program, mentioning Metro as one of "the district's three major alternative programs".

As we can see in this last article, "one reason for the magnet school proposal [was] an effort to achieve better racial integration", but Metro already had racial integration as part of its guiding precepts, and always worked to keep the black/white racial balance as close to 50/50 as possible--Betty's vision brought this concept to the SLPS, it did not bring it to her. This, in fact, is what the design of the Metro High School symbol, still used today, showed: a black and a white arm, reaching up to clasp hands in unity. When a later principal at Metro, after Betty's retirement, suggested a re-tooling of this design, to maybe provide a more refined, computer-generated image, the teachers who had been at Metro during Betty's years, spoke up passionately in favor of keeping the original design, as it had been conceived of, and produced by students in the first year of Metro's existence, and was a strong symbol of what Metro stood for: a school for students of vision, of intelligence, who believed in unity, and who had a hand in their own education. It incorporates Metro's original colors-- black and white -- with the added "touch of gold" that Betty chose as the third color when Metro was renamed Metro Academic and Classical High School, in 1996.

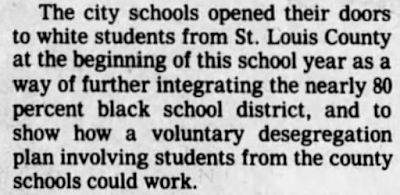

The history of the St.-Louis-City-only Magnet schools, and how they developed into the Magnet schools that later included St. Louis County students (the VICC program), is complicated and lawsuit-driven, but Metro's part of that history can be summarized by saying that it began as an Alternative city school, was then absorbed into the SLPS's city magnet schools, and then, in 1981, became one of the Federally mandated City-County voluntary desegregation program schools.

The 1980s (The Temple Israel House years)

The initial desegregation program within the City of St. Louis, sought to integrate SLPS buildings, which had grown to be as segregated as the city neighborhoods they served. The original Magnet Schools program, as described here and here in 1976, was for St. Louis City residents, and was only open to St. Louis County residents who were willing to pay a yearly tuition to attend (but few, if any, did so). The program expanded in 1981, to include St. Louis County school districts (now at no tuition cost to County parents), with the idea that the SLPS/City schools, whose student population was about 80% black, would get an influx of white students from the primarily-white St. Louis County schools who participated, and those primarily-white schools, would benefit from the integration of black students who lived in the city of St. Louis. Racial integration and racial harmony and expanded educational opportunities were all the key factors driving the "deseg plan", as it was commonly called.

As a result of Metro becoming a part of the expanded city/county Magnet school program, Betty was forced to put on her thinking cap once again, to re-tool her beloved Metro, with a mind to keeping as much of what worked well of the "school without walls" concept, while adapting it into a school which could be a strong pull for attracting County students. The new version of the Magnet program required Metro to enlarge, and accept almost twice the number of students, but Betty succeeded in capping that number at 240. To accommodate the increased enrollment, and re-focused concept of the school, Metro was given a new home in the old Temple Israel House building at 5017 Washington, in the city's Central West End. The location had previously been used as the short-lived city magnet Business and Office High School .

The new focus of Metro would still include classes taken at locations off-campus (there were Spanish classes with Mrs. Rehkemper at St. Louis University's campus, and Algebra classes at the Harris Stowe College campus, as well as Art History classes at the The St. Louis Art Museum, for example, and a very popular course called Outdoor Ed, saw students participating in campouts, hiking adventures, and exploration of noted city cemetaries), but the focus of the school became less "school without walls" and more "college prep", however, with Betty at the helm, the emphasis was still squarely on the student, still instilling and developing in them a strong appreciation for exploring to learn, excelling by choice, and improving their community. As such, Metro remained a school without bells, with college-type scheduling, and an open campus. The new location on Washington allowed for Metro's adventurous students to venture off to Duff's for an after-school meal, or stop in at one of the area fast-food restaurants for lunch. They hung out on the grass outside, between classes in the nice weather, or congregated in the large "multi-purpose room" on the first floor of the building, where lockers, lunch tables, and assembly gatherings were found.

Three other components of Betty's Metro, were crucial to its success as it continued to thrive throughout the 1980s:

The Entrance and Exit policies were part of the heart and soul of the academic strength of Metro. As Betty had shown early on in the development of Metro, its success hung partly on the ability to save slots at this alternative type of school, for students who had it within themselves to really dig in and thrive in an atmosphere of strong, intelligent curiosity, and who were ready and willing to devote themselves fully to growing, for themselves, and for their community. Betty sought, and was awarded, the right to hold students accountable for continuing this kind of academic rigor and personal growth. To that end, Metro initiated an "Exit Policy", which held that a student who did not keep up a responsible attitude toward academics, would not be allowed to continue taking up a coveted spot at the school. Students adhered to an A-B-C grading scale, with no passing grade given for courses finished with a grade lower than 70%, and were placed on Academic Probation if grades slipped. There was a set required curriculum for all four years at Metro, and there was not, realistically, any way for a student to take over courses that they failed, the following year. Because of that, if a student could not make up for a failed course, through taking a standard summer-school version of it at one of the SLPS summer schools, they could not return to Metro. Since there was a limit of 2 summer-school classes per summer, in the district, if a student failed three courses in a school year, they could not return to Metro the following year. Most students learned early on, during freshman year, whether or not they had the heart and mindset to be a Metro student for four years.

Academically, there were courses that were only really available at Metro, and requirements that were not in place at other area high schools. As Metro became fully devoted to being a school to prepare intellectually inquisitive students for higher education, there was an inclusion early on of a pair of classes, taken during sophomore year, called, Testing English and Testing Math. Each of these semester courses prepared the students with a strong knowledge base in the kind of material and the kind of analytical thinking skills required for success on the ACT and SAT tests for college-bound students. Mrs. Heloise Mayer, the long-time teacher of the Testing English class was notorious for chanting the admonition to "Read, read, read, and read." In fact, all of the teachers encouraged and rewarded opportunities for further learning through self-chosen reading, with Social Studies teacher Tom Morgan leading the pack. Tom had a wall full of books that he picked up at the Book Fair and from donations from friends, and from perusing flea markets and used book stores, and he provided for-credit opportunities for students who chose books related to the class topics, to read further on their own.

Two other semester-long courses were required for graduation from Metro: Art Appreciation and Music Appreciation. Betty had a clear understanding that a development in the arts was necessary for appreciating life fully and growing as a person. She knew, from speaking to successful business leaders, that knowledge in these areas would be beneficial, and expected, for anyone moving in the business and professional circles that Metro students were destined to join as they moved on with their lives after high school.

Foreign language was a two-year minimum requirement at Metro, as well, and that was two years from whatever level a student began at, as a freshmen. As many of the Metro students began foreign language in middle school, if they came to Metro from the SLPS Classical Junior Academy, as many did, that usually meant that they finished high school with the successful completion of at least level-three French, Spanish, or Latin. This was a plus for students interested in applying to some of the highly-competitive, high-standard four-year universities that many were headed for: Duke, Harvard, Stanford, Smith, Emory, Washington University, and the like. Not all Metro students finished their education at those big-name schools, but many of them did, and they did so, in most all cases, with well-earned full-ride scholarships. Metro, in fact, developed a reputation among quality universities, as a public school that graduated highly capable, analytical, inquisitive, well-prepared, and self-motivated learners.

Finally, one of the funny misconceptions about Metro, was that it had no athletic program. This was probably the result of the fact that it had no Football program, but Metro students were no slouches in the world of high-school athletics. Students competed in, and excelled in, Cross Country, Track, Baseball, Volleyball, Tennis, and Basketball. The joke, it was said, was that what distinguished Metro's athletes from those at some of the schools they competed against, was that they did their homework between at-bats, and, instead of throwing punches at aggressors, they threw calculators. Metro students reveled in being academic rebels, and in making their way in the world with humor, grace, and intelligence.

The 1990s and Beyond (The McPherson years)

In the early 1990s, Betty accomplished one last monumental feat for her students: she successfully lobbied the St. Louis Public Schools to provide Metro students with a new-construction building, to reward them, and Metro's staff, for continuously providing the highest test scores in the district (in the state, in fact), and graduating scores and scores of well-educated students, who would go on to become highly accomplished adults, giving back not only to the St. Louis area community, but to the national and global community.

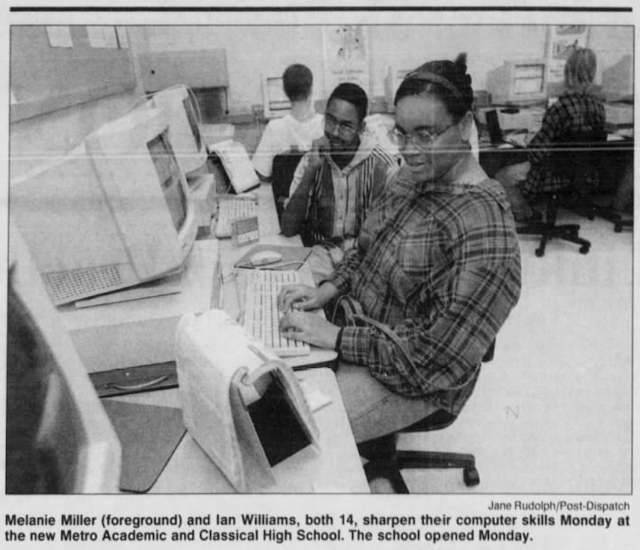

In 1995, Metro's students and staff watched as a new building was designed, and learned that ground was broken on McPherson Avenue, on the site of a former SLPS building that was slated for demolition. That year, throughout the spring semester, teachers worked to pack up their classrooms, in anticipation of everything being moved over the summer of 1996, to the new building. As fate would have it, however, the start of the school year arrived, and the new building was not yet ready for occupation. A mortified staff and student body was forced to start the new school year digging, daily, through boxes, to find textbooks and chalk and pencil sharpeners and blue mimeograph pages. But, finally, in October of that year, the move happened, and on a crisp, bright fall day, in October of 1996, Metro's students began their day at a brand new building on McPherson Avenue.

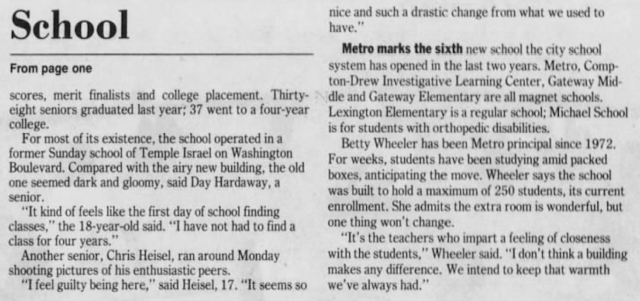

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch did a few articles that fall, about Metro's move to its new building, and Betty's role at the helm since 1972. The October 22, 1996 issue had this story:

For the first time ever, Metro High School Panthers had their own gym (for years, the students had done gym class outside, running in the Central West End neighborhood, working out in the parking lot, or learning team sports in borrowed space in the church building across the street on Washington Blvd.), and finally had a real computer lab, as well as six computers per classroom, to help students usher in the new world of learning with computers and Internet access. What we don't see in the photos, was the addition of a true auditorium, as well, which Betty was determined to have for her students. Since 1981, they had used the multi-purpose room in the old building for multiple purposes -- tables and chairs were in place for lunch time and gathering between classes, and, when speakers or talent shows or parent meetings were scheduled, the tables were cleared away and stacked to the sides, and two hundred chairs were set up, so that the big stage at the far end of the room could become center stage, so to speak. Now, in the new building, a state-of-the-art, honest-to-God auditorium, with upholstered seats and computer-run sound system, would be the site of future National Honor Society inductions, school plays, and presentations by guest speakers. A few years after Betty retired, the auditorium was officially re-named the Betty McNeal Wheeler Auditorium, with a large, bronze plaque declaring it so, just outside its double-door entrance.

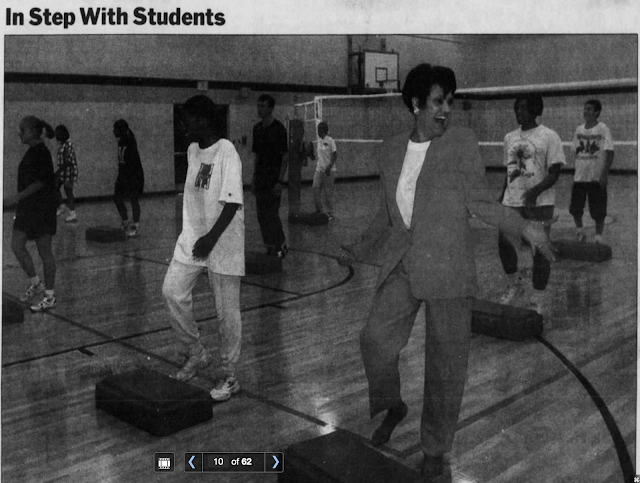

Another article, especially focusing on Betty and her past as the founding principal of Metro, was published in the Post-Dispatch on October 27, 1996. Betty, always impeccably dressed, was shown in all her glory, joining in on a step-aerobics gym class, in the new gym:

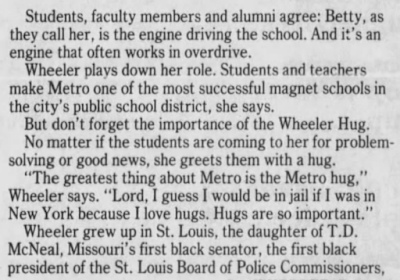

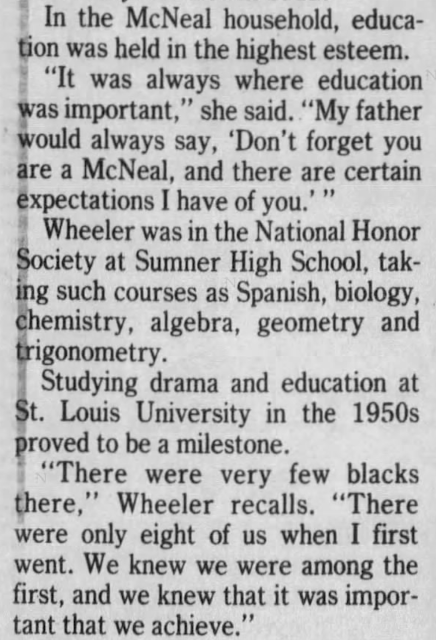

The article also highlighted Betty McNeal Wheeler's background, and noted the importance of father, T.D. McNeal, in her life, and in the life of Missouri:

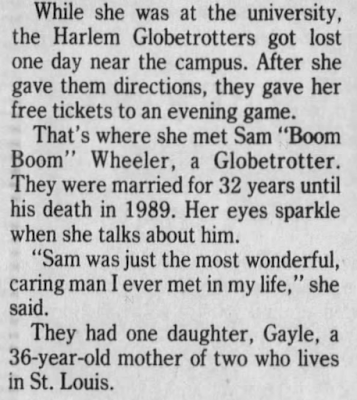

And, about her personal life, it also mentioned Sam Wheeler, Betty's husband, a former Harlem Globetrotter, and their daughter, Gayle:

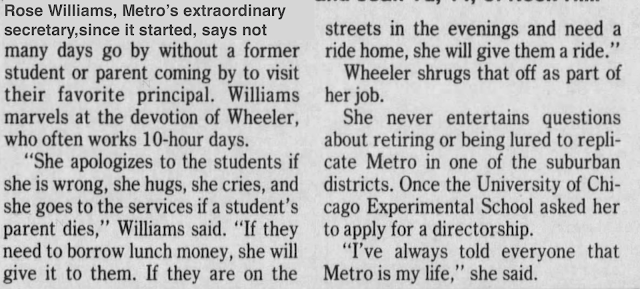

Finally, the story wrapped up with comments from Rose Williams, who was Metro's secretary -- really, she was Betty's main assistant and co-runner of the school-- from its first days in 1972, through into the 1990s:

No story about Metro High School, would be complete without mention of Rose Williams. Rose was hand-picked by Betty, in 1971, to be her right-hand-woman, to help her run Metro. Her job was labeled "secretary", but she was, without a doubt, the back to Betty's front, so to speak. Together, they formed an incredibly approachable, patient, and amazingly accomplished duo, who took care of every aspect of running Metro, without the help of computers, a vice principal, secondary secretaries, a data runner, or an attendance officer. Rose knew every student's name -- for years after they graduated-- knew their siblings' names, knew their parents' names, and discreetly took the time to realize what each one needed for success, and what kind of helpful hand they might need. She and Betty discreetly helped students, over the years, who encountered personal troubles -- never sharing that information, or holding it out for praise, but it happened. When Rose finally retired, in the late 1990s, her position was filled by three professionals... who also had the help of computerized database systems. Rose Williams, to put it plainly, was the most accomplished co-CEO of a school who ever wore the label "secretary".

Betty McNeal Wheeler retired at the close of that first school year in the new building, shocking her entire faculty with the news that it would be her last year. But, she had brought Metro through decades of success, molding it and adapting it to continued success through major changes, and finally ushered in a new generation, in a new building, and had achieved what she set out to do. What makes her unique, is the role that she had in shaping the most successful school in the history of the St. Louis Public Schools, and with that, the lives of hundreds upon hundreds of bright, promising young minds, who didn't even realize how much they yearned to soar. Betty gave them wings, and all of the personal and intellectual tools that they would need to move forth and give back to themselves, and to their society.

Through the years, Metro graduates have done remarkable things, and they are Betty McNeal Wheeler's legacy. Betty always underscored the idea that no one should be held out for special recognition, when everyone was excelling... so, we won't mention every Metro graduate's accomplishments. We can't, in any case, because there are so many. But, among them are countless educators, at every level of schooling; PhDs; MDs; authors of published articles, books and doctoral theses; elected officials; a chief of police of St. Louis; a director of revenue for the state of Missouri; entrepreneurs of million-dollar businesses; recipients of St. Louis Business awards; community leaders; Grammy nominees; art award recipients; national and international journalists; regional Emmy-winning television producers; professional photographers; and international federal attorneys. To name a few. The point is: Metro has had a long history of educating -- truly, really educating -- people who came there with remarkable abilities, to begin with, and they have gone forth, after Metro, to do more remarkable things for our society. It is a testament to the kind of education that Metro High School offered, that these kinds of people were well served by their Metro education. The thanks and recognition all fall squarely on the back of Betty McNeal Wheeler.

Betty McNeal Wheeler passed away, with Rose Williams at her side, on May 19, 2011. Her obituary can be found here.

Epilogue

Metro Academic & Classical High School (as it was re-named when it was given its new location on McPherson Avenue), has continued to soar since Betty Wheeler put in motion its successful path, and guided it along its way for 25 years. One of Betty's hopes, was for Metro to one day become an International Baccalaureate High School, but, when she discussed the idea with her faculty, in the early 1990s, she knew that the school, in the building where it stood, was limited in some of the required facilities that an International Baccalaureate school would require. So, after accomplishing the goal of seeing Metro into its new facility, Betty focused the search for a new principal, on someone who would be ready and willing to help guide the faculty to put together the application process for Metro to become an I.B. World school. That goal was accomplished by Betty's faculty, and their new principal, Pamela Randall, who also all worked together to attain Blue Ribbon and Gold Star status for the school. In the years since, Metro has gone on to have three new principals, Wilfred "Doug" Moore, Steven Lawler, and Dr. Tina Wallace-Hamilton (who began in the 2022-23 school year). For many years, Metro has ranked as the No. 1 public high school in the State of Missouri, for test scores, and has continuously ranked in the top 150 high schools in the nation, in ratings in Newsweek and US News and World Report magazines. (See Metro's Wikipedia article, here, with references and basic statistics about the school.)

*This article was researched and written by Judith E. Chabot, French teacher at Metro High School from 1984-2003. It is dedicated, with deep and sincere gratitude and appreciation, to Betty McNeal Wheeler, and the role that she played in guiding her as a teacher, and as a woman.

This is how Metro began, but it evolved over the years, always under the careful guidance of Betty's ideas of how it could best serve the students and their community.

The 1970s (The Chouteau Avenue years)

|

| Philadelphia Inquirer, May 11, 1970 |

Philadelphia had its Parkway High School Without Walls, whose name was inspired by the view of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway...and the Art Museum...and all of the buildings around the city of Philadelphia... that Clifford Brenner, director of development, could see from his office window, and that he suggested should be, could be, used as the "classroom" for motivated students.

Chicago had its own Metro High: Chicago Public High for Metropolitan Studies (though it appears that everyone called it, lovingly, Metro!! The School Without Walls!). The 1970 video, here, on the Chicago Film Archives web page, describes the early structure for Chicago's Metro High. One of the adults interviewed, mentions that its philosophy is to combine the interests and ideas of students, with the experience and judgement of what works, of the educators, emphasizing that students have great input, but do not "run the show", as some community members were fearful would be the case. The commentary in the video takes great pains to emphasize the community nature of Chicago's Metro High, that exploring and learning from what is available in the community, and learning to appreciate the community, were at the heart of the tenets of the school.

|

| You can find this video here, about midway through the page |

Betty Wheeler's strength, in designing St. Louis's Metro High, was in her innate understanding that this concept could work, but only with more careful planning, and with a constant eye on what was working, and what might not. She said, in an interview in April of 1972, about the upcoming opening of the school, in fall of 1972, that she felt that the key to putting together a really viable version of a community-based school without walls, was in the planning, and that she felt that the reason that other schools that had tried this idea, had not worked out in the long run, was because the staff was not given enough time to fully flesh out the plans, carefully. Here are a few snippets from the newspaper article, St. Louis To Try Out A Classroom As Big As The City, published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 11, 1972:

One of the key areas to which Betty gave a good bit of thought, was the idea of who would be accepted as students in St. Louis's Metro High. She understood that one of the weaknesses of the Philadelphia program, for example, was how it got its students. That school used a simple lottery system, and students were referred if they seemed to have a difficulty accepting the norms of a traditional school. Not as much thought seemed to be given, in Philadelphia, to the motivation and abilities of the students. Betty's Metro High would more carefully organize their selection process: the school would focus on students who were deemed most capable of taking advantage of the freedoms and unconventional structure that the school without walls would provide. They needed to show a strong academic ability, along with a heart that yearned for exploration and a soul that would soar when given the opportunity to grow through a non-traditional structure. Students were asked to write essays about why they felt that Metro would be a great fit for them, and test scores and personal references from their current schools, were evaluated. Additionally, Metro was meant to be a place to bring together and celebrate students from the black community, and from the white community, from all over the city, at a time when racial integration in the schools was a new concept, striving for success, and desperately needed in the St. Louis community. This was also a time when the voices of women in the United States were beginning to be heard, and this, too was to be part of Metro High's mission: to celebrate all segments of our society, by living and working together, thereby providing a natural growth of appreciation and respect for each other.

And, from a 1974 article about Metro's first graduation:

|

| St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 28, 1974 |

As Metro continued its School Without Walls concept throughout the 1970s, it grew to accept all four grades (its first years saw the inclusion of students only in the 11th and 12th grades), but it was billed as an Alternative School, not a Magnet school, as the Magnet School program did not begin in St. Louis until late 1976. Two articles in the February 1, 1976 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, both on page 3G, discuss Alternative Schools, and mention Metro. Betty is quoted in this extensive article about Alternative Schools, about the concept of keeping the schools small -- this was always a key issue for Betty, as she understood, from research as well as practice, that students were best served in small schools, rather than in large ones.

The second article on that page (Magnet School As Alternative) describes the plans for the upcoming Magnet Schools program, and the value of incorporating the existing alternative programs, into the Magnet program, mentioning Metro as one of "the district's three major alternative programs".

|

| These paragraphs are snipped from the original, longer, article • 1976 • St. Louis Post-Dispatch |

As we can see in this last article, "one reason for the magnet school proposal [was] an effort to achieve better racial integration", but Metro already had racial integration as part of its guiding precepts, and always worked to keep the black/white racial balance as close to 50/50 as possible--Betty's vision brought this concept to the SLPS, it did not bring it to her. This, in fact, is what the design of the Metro High School symbol, still used today, showed: a black and a white arm, reaching up to clasp hands in unity. When a later principal at Metro, after Betty's retirement, suggested a re-tooling of this design, to maybe provide a more refined, computer-generated image, the teachers who had been at Metro during Betty's years, spoke up passionately in favor of keeping the original design, as it had been conceived of, and produced by students in the first year of Metro's existence, and was a strong symbol of what Metro stood for: a school for students of vision, of intelligence, who believed in unity, and who had a hand in their own education. It incorporates Metro's original colors-- black and white -- with the added "touch of gold" that Betty chose as the third color when Metro was renamed Metro Academic and Classical High School, in 1996.

The history of the St.-Louis-City-only Magnet schools, and how they developed into the Magnet schools that later included St. Louis County students (the VICC program), is complicated and lawsuit-driven, but Metro's part of that history can be summarized by saying that it began as an Alternative city school, was then absorbed into the SLPS's city magnet schools, and then, in 1981, became one of the Federally mandated City-County voluntary desegregation program schools.

|

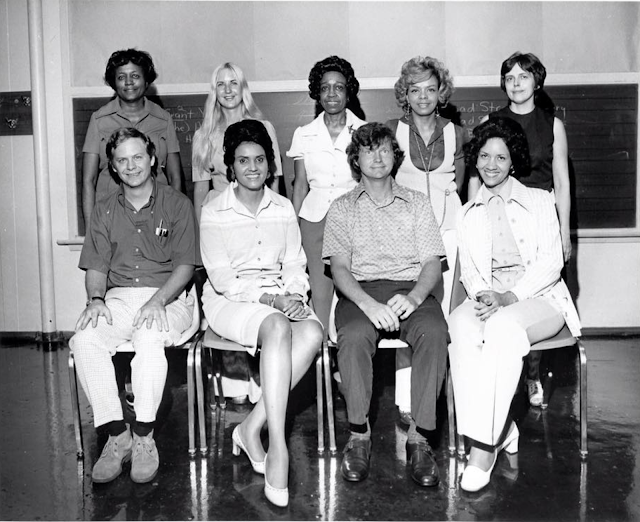

| Betty M. Wheler and her hand-chosen faculty, in 1972 |

The 1980s (The Temple Israel House years)

|

| Metro High School's new location, beginning fall of 1980: 5017 Washington, the former "Temple Israel House" |

|

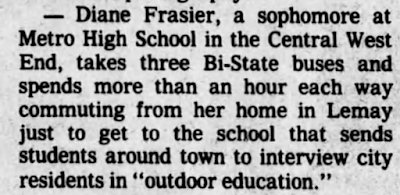

| Both of these snippets are from this 1981 source . |

The new focus of Metro would still include classes taken at locations off-campus (there were Spanish classes with Mrs. Rehkemper at St. Louis University's campus, and Algebra classes at the Harris Stowe College campus, as well as Art History classes at the The St. Louis Art Museum, for example, and a very popular course called Outdoor Ed, saw students participating in campouts, hiking adventures, and exploration of noted city cemetaries), but the focus of the school became less "school without walls" and more "college prep", however, with Betty at the helm, the emphasis was still squarely on the student, still instilling and developing in them a strong appreciation for exploring to learn, excelling by choice, and improving their community. As such, Metro remained a school without bells, with college-type scheduling, and an open campus. The new location on Washington allowed for Metro's adventurous students to venture off to Duff's for an after-school meal, or stop in at one of the area fast-food restaurants for lunch. They hung out on the grass outside, between classes in the nice weather, or congregated in the large "multi-purpose room" on the first floor of the building, where lockers, lunch tables, and assembly gatherings were found.

|

| This snippet is from a September 1984 St. Louis Post-Dispatch article, available here. |

- Community Service

- Entrance requirement

- Exit policy

The Entrance and Exit policies were part of the heart and soul of the academic strength of Metro. As Betty had shown early on in the development of Metro, its success hung partly on the ability to save slots at this alternative type of school, for students who had it within themselves to really dig in and thrive in an atmosphere of strong, intelligent curiosity, and who were ready and willing to devote themselves fully to growing, for themselves, and for their community. Betty sought, and was awarded, the right to hold students accountable for continuing this kind of academic rigor and personal growth. To that end, Metro initiated an "Exit Policy", which held that a student who did not keep up a responsible attitude toward academics, would not be allowed to continue taking up a coveted spot at the school. Students adhered to an A-B-C grading scale, with no passing grade given for courses finished with a grade lower than 70%, and were placed on Academic Probation if grades slipped. There was a set required curriculum for all four years at Metro, and there was not, realistically, any way for a student to take over courses that they failed, the following year. Because of that, if a student could not make up for a failed course, through taking a standard summer-school version of it at one of the SLPS summer schools, they could not return to Metro. Since there was a limit of 2 summer-school classes per summer, in the district, if a student failed three courses in a school year, they could not return to Metro the following year. Most students learned early on, during freshman year, whether or not they had the heart and mindset to be a Metro student for four years.

Academically, there were courses that were only really available at Metro, and requirements that were not in place at other area high schools. As Metro became fully devoted to being a school to prepare intellectually inquisitive students for higher education, there was an inclusion early on of a pair of classes, taken during sophomore year, called, Testing English and Testing Math. Each of these semester courses prepared the students with a strong knowledge base in the kind of material and the kind of analytical thinking skills required for success on the ACT and SAT tests for college-bound students. Mrs. Heloise Mayer, the long-time teacher of the Testing English class was notorious for chanting the admonition to "Read, read, read, and read." In fact, all of the teachers encouraged and rewarded opportunities for further learning through self-chosen reading, with Social Studies teacher Tom Morgan leading the pack. Tom had a wall full of books that he picked up at the Book Fair and from donations from friends, and from perusing flea markets and used book stores, and he provided for-credit opportunities for students who chose books related to the class topics, to read further on their own.

Two other semester-long courses were required for graduation from Metro: Art Appreciation and Music Appreciation. Betty had a clear understanding that a development in the arts was necessary for appreciating life fully and growing as a person. She knew, from speaking to successful business leaders, that knowledge in these areas would be beneficial, and expected, for anyone moving in the business and professional circles that Metro students were destined to join as they moved on with their lives after high school.

Foreign language was a two-year minimum requirement at Metro, as well, and that was two years from whatever level a student began at, as a freshmen. As many of the Metro students began foreign language in middle school, if they came to Metro from the SLPS Classical Junior Academy, as many did, that usually meant that they finished high school with the successful completion of at least level-three French, Spanish, or Latin. This was a plus for students interested in applying to some of the highly-competitive, high-standard four-year universities that many were headed for: Duke, Harvard, Stanford, Smith, Emory, Washington University, and the like. Not all Metro students finished their education at those big-name schools, but many of them did, and they did so, in most all cases, with well-earned full-ride scholarships. Metro, in fact, developed a reputation among quality universities, as a public school that graduated highly capable, analytical, inquisitive, well-prepared, and self-motivated learners.

Finally, one of the funny misconceptions about Metro, was that it had no athletic program. This was probably the result of the fact that it had no Football program, but Metro students were no slouches in the world of high-school athletics. Students competed in, and excelled in, Cross Country, Track, Baseball, Volleyball, Tennis, and Basketball. The joke, it was said, was that what distinguished Metro's athletes from those at some of the schools they competed against, was that they did their homework between at-bats, and, instead of throwing punches at aggressors, they threw calculators. Metro students reveled in being academic rebels, and in making their way in the world with humor, grace, and intelligence.

|

| A beautiful photo of Betty McNeal Wheeler, in the 1980s, in her office at Metro High School. |

|

| Metro Academic & Classical High School • 4015 McPherson Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri |

In 1995, Metro's students and staff watched as a new building was designed, and learned that ground was broken on McPherson Avenue, on the site of a former SLPS building that was slated for demolition. That year, throughout the spring semester, teachers worked to pack up their classrooms, in anticipation of everything being moved over the summer of 1996, to the new building. As fate would have it, however, the start of the school year arrived, and the new building was not yet ready for occupation. A mortified staff and student body was forced to start the new school year digging, daily, through boxes, to find textbooks and chalk and pencil sharpeners and blue mimeograph pages. But, finally, in October of that year, the move happened, and on a crisp, bright fall day, in October of 1996, Metro's students began their day at a brand new building on McPherson Avenue.

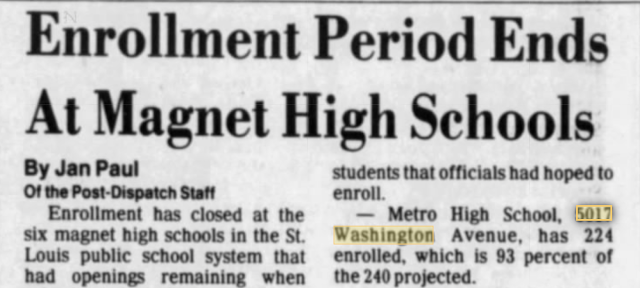

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch did a few articles that fall, about Metro's move to its new building, and Betty's role at the helm since 1972. The October 22, 1996 issue had this story:

|

| St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 22, 1996, page B1 |

|

| St. Louis Post-Dispatch story, Oct 22, 1996, continued |

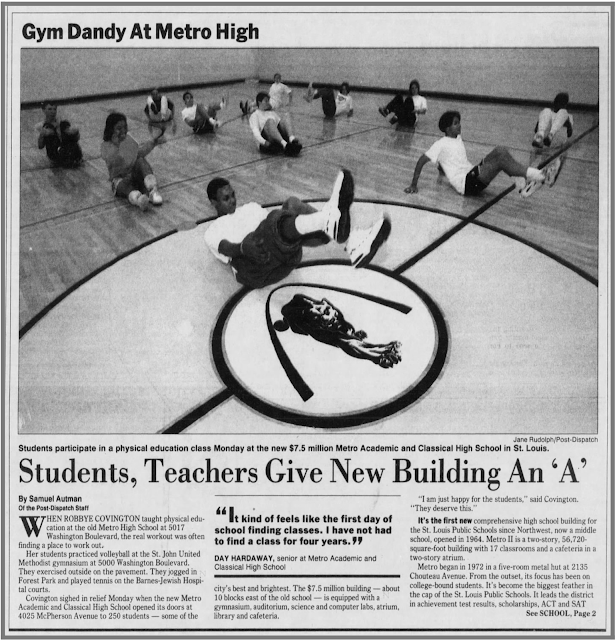

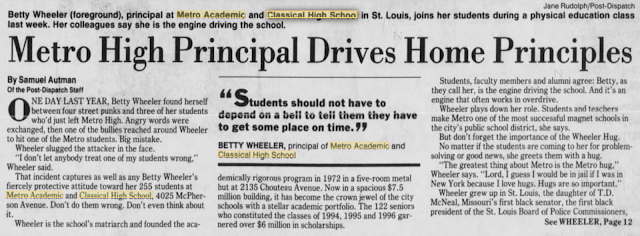

Another article, especially focusing on Betty and her past as the founding principal of Metro, was published in the Post-Dispatch on October 27, 1996. Betty, always impeccably dressed, was shown in all her glory, joining in on a step-aerobics gym class, in the new gym:

|

| October 27, 1996 • St. Louis Post-Dispatch, page D1 |

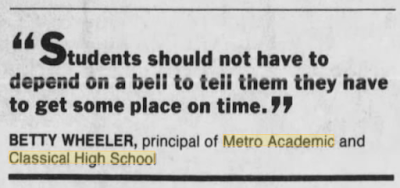

In reference to the no-bell policy and open-campus policy of Metro, Betty mentioned, as she had said before, that college-bound students who were headed to become responsible members of society, should not need bells to tell them that they have to get someplace on time.

Betty also made reference to her famous Metro Hug -- Betty much preferred to hug you, than to be-rate you. She understood that you deserved a hug if you had accomplished something, but that you also probably needed a hug, if you had done something uncharacteristically inappropriate... so, that was often her first, and disarming, approach to a problem she and a student (or staff member) might encounter.

The article also highlighted Betty McNeal Wheeler's background, and noted the importance of father, T.D. McNeal, in her life, and in the life of Missouri:

And, about her personal life, it also mentioned Sam Wheeler, Betty's husband, a former Harlem Globetrotter, and their daughter, Gayle:

Finally, the story wrapped up with comments from Rose Williams, who was Metro's secretary -- really, she was Betty's main assistant and co-runner of the school-- from its first days in 1972, through into the 1990s:

|

| All of these last snippets are from the second part of this October 27, 1996 newspaper story in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch |

Betty McNeal Wheeler retired at the close of that first school year in the new building, shocking her entire faculty with the news that it would be her last year. But, she had brought Metro through decades of success, molding it and adapting it to continued success through major changes, and finally ushered in a new generation, in a new building, and had achieved what she set out to do. What makes her unique, is the role that she had in shaping the most successful school in the history of the St. Louis Public Schools, and with that, the lives of hundreds upon hundreds of bright, promising young minds, who didn't even realize how much they yearned to soar. Betty gave them wings, and all of the personal and intellectual tools that they would need to move forth and give back to themselves, and to their society.

Through the years, Metro graduates have done remarkable things, and they are Betty McNeal Wheeler's legacy. Betty always underscored the idea that no one should be held out for special recognition, when everyone was excelling... so, we won't mention every Metro graduate's accomplishments. We can't, in any case, because there are so many. But, among them are countless educators, at every level of schooling; PhDs; MDs; authors of published articles, books and doctoral theses; elected officials; a chief of police of St. Louis; a director of revenue for the state of Missouri; entrepreneurs of million-dollar businesses; recipients of St. Louis Business awards; community leaders; Grammy nominees; art award recipients; national and international journalists; regional Emmy-winning television producers; professional photographers; and international federal attorneys. To name a few. The point is: Metro has had a long history of educating -- truly, really educating -- people who came there with remarkable abilities, to begin with, and they have gone forth, after Metro, to do more remarkable things for our society. It is a testament to the kind of education that Metro High School offered, that these kinds of people were well served by their Metro education. The thanks and recognition all fall squarely on the back of Betty McNeal Wheeler.

Betty McNeal Wheeler passed away, with Rose Williams at her side, on May 19, 2011. Her obituary can be found here.

Epilogue

Metro Academic & Classical High School (as it was re-named when it was given its new location on McPherson Avenue), has continued to soar since Betty Wheeler put in motion its successful path, and guided it along its way for 25 years. One of Betty's hopes, was for Metro to one day become an International Baccalaureate High School, but, when she discussed the idea with her faculty, in the early 1990s, she knew that the school, in the building where it stood, was limited in some of the required facilities that an International Baccalaureate school would require. So, after accomplishing the goal of seeing Metro into its new facility, Betty focused the search for a new principal, on someone who would be ready and willing to help guide the faculty to put together the application process for Metro to become an I.B. World school. That goal was accomplished by Betty's faculty, and their new principal, Pamela Randall, who also all worked together to attain Blue Ribbon and Gold Star status for the school. In the years since, Metro has gone on to have three new principals, Wilfred "Doug" Moore, Steven Lawler, and Dr. Tina Wallace-Hamilton (who began in the 2022-23 school year). For many years, Metro has ranked as the No. 1 public high school in the State of Missouri, for test scores, and has continuously ranked in the top 150 high schools in the nation, in ratings in Newsweek and US News and World Report magazines. (See Metro's Wikipedia article, here, with references and basic statistics about the school.)

|

| Rose Williams and Betty McNeal Wheeler, in Betty's office in Metro's new McPherson avenue building, 1997. |

*This article was researched and written by Judith E. Chabot, French teacher at Metro High School from 1984-2003. It is dedicated, with deep and sincere gratitude and appreciation, to Betty McNeal Wheeler, and the role that she played in guiding her as a teacher, and as a woman.